| |

4. Appropriate language: mind the register

You talk with your professor in a different way than you do with your friends, even about the same topic. You talk to the same professor again in a different manner depending on whether you meet for a seminar or accidently run into each other in a queue at the cafeteria. You use different vocabulary in an essay than in a personal e-mail, and so on. All this has to do with the style, or more precisely, with the register. Register refers to the way in which language is shaped by its subject but also its purpose, medium, addresser and addressee.

Academic register. Academic English is formal by nature. However, this does not mean that it should be stilted: stiffly formal and unnatural. Mastering the academic style requires a good knowledge on the typical traits of the register, as well as an understanding of grammatical structures and word formation. The previous chapter started the work on word formation, and this final chapter of the VIEW section introduces other ways of using the corpus for improving your academic English.

A. Common words in the academic register

The registers allow you to limit your search within a specific register. You can benefit from this in your own learning: knowing the most common words in a register helps you to use English in a more appropriate and accurate way. The people who speak English as their own language are exposed to the vocabulary and structures of the language all their lives, and develop a more or less thorough understanding of the registers naturally. For learners of English this usually takes more time and effort, as an understanding of even one register requires a regular contact with suitable language items. Using a corpus can offer a shortcut to this kind of understanding, as it enables you to select the language items and the register you are wanting to learn.

Try it yourself!

Read the general instructions first and then run searches on the language items

listed below. Remember to reset your search settings before starting a new search.

- Don't write anything in the search string box, but from the Insert tag menu underneath select a POS-tag of you choice .

- At the Register 1 panel, select ACADEMIC from the scroll menu.

- You can also try the search with one of the subregisters that can be found towards the end of the scroll menu. For example W_ac_soc_science limits the search to the written texts from the social sciences domain, and S_lect_humanities_arts gives results from lectures on humanities and arts.

Following the instructions above, examine the academic register by looking up the most typical members in some of the word classes, for example

- adjectives (tag adj.ALL or [aj*])

- verbs (tag verb.ALL or [v*])

Notice also, that the first ten or twenty items listed in the search results are often common to English in general - for example adverbs more, only and also; and verbs make, be and do. With verbs you may also use the tag verb.LEX that omits verbs such as have and be from the results.

Good to know.

Each register is divided into subregisters: in the academic domain you have for example law and education, natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities and arts separated as subregisters; under spoken language you can find for instance lectures from several domains, broadcast discussions, religious sermons, and courtroom interactions. Exploring the sub- registers can give you precise information on the vocabulary, structures and language use in a specific context.

B. Comparison between two registers

A good way of getting to grips with the qualities of the academic register is to compare it with something to which it contrasts. For example, the journalistic register makes use of colourful adjectives and short paragraphs which intend to grab the readers' attention, which is not typical for the academic style. The VIEW offers a possibility of comparing the use and frequency of language items between two registers, thus helping you to understand their characteristics.

Try it yourself!

We'll try a comparison between the academic and the fiction registers with two language items, and see what they can tell about the two registers. Here are the general instructions:

- Select the POS-tag from the Insert tag drop-down menu.

- Under the Register 1 panel choose ACADEMIC.

- Click Search.

- Run the same search again, but this time set Register 1 to FICTION.

- Compare the results.

The language items we are going to look at are

- the negative form (not, n't) - tag neg.ALL or [xx0]

- personal pronouns - tag pron.ALL or [pn*]

Read the questions in the text field below, and go to the VIEW to run the first two searches: the negative in the academic and in the fiction register. Answer the questions 1 and 2, writing your comments in the text field. Do the same again with pronouns, and come back to answer questions 3, 4, and 5. When ready, click Bernie the Owl for feedback.

C. Comparison across the registers

The VIEW makes it possible also to compare the occurrence of a word, expression, class of words and grammatical structures across registers. The main division in VIEW is between spoken, fiction, news and academic registers. The comparison of registers is valuable in particular for learners, as the information gained ressembles the understanding of the language use the native speakers of the language have.

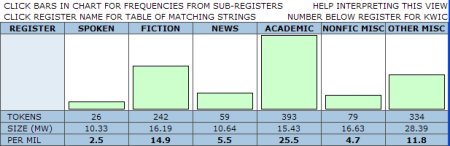

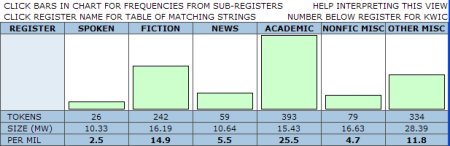

The search results for this across the registers are presented in a form different from what you are used to. The results appear in the upper main frame of the VIEW in the form of a chart, looking like this:

From the chart above we can conclude for example, that the search item is far more common in the academic than in any other register (25.5 per million), and that in the spoken register it can be rarely found (26 instances, 2.5 per million). Clicking the light green bars shows you how the search item is divided in the sub-registers of the particular register. By clicking the register names you get a list of matches in that particular register, and clicking the listed items there gets you to the KWIC-lists.

Try it yourself!

We'll try a search with some language items to see how they are spread across the registers. The general adjustments needed for comparison are the following:

- Type the search string in the usual textfield, or select a word class (POS-tag) from the drop-down menu

- Under Display panel, select Chart

- Click Search

- Make sure to reset the search settings before running an other search, as clicking the charts to browse the search results changes the settings

Following the instructions above, run a search across the registers with the following language items and consider the questions below. When ready, click Bernie the Owl for feedback.

- lexical verbs (tag verb.LEX or [vv*])

- the past participle of lexical verbs , eg. forgotten (tag verb.EN or [v?n])

What do the results tell you about the use of verbs in the academic register?

What do you think explains the frequency of the past partciple in the academic register?

Search tip.

You'll get more information by clicking the register name above the chart and accessing a KWIC-list through the listed items.

For corpus enthusiasts

D. Two options for comparing the use of synonyms in registers

Good to know.

For comparing between registers there are two options that provide a bit different information from one another. The first option is to run a search with the word, phrase or POS-tag first in one register and then in the other, and compare the results, as you did just above in B. The second option is to select the register you are interested in as Register 1, and select the register to which you want to make the comparison as Register 2. This option gives you information on the ratio of the search item between the two registers. The search task below will give you an idea of what this is all about.

Try it yourself!

Option 1. To get started on this final exercise, we'll try a search according to the first option presented in the tip box just above. Instead of using individual words, phrases or POS-tags we'll try a simultaneous search with five verbs that often are used for same purpose and have a similar meaning. Follow the instructions below:

- Copy the search string and paste it in the search string box

guess/suppose/imagine/estimate/infer

- Under the Register 1 panel choose ACADEMIC.

- Click Search.

- Type the verbs in their listed order to the assigned textbox below.

- Run the same search again, but this time set Register 1 to SPOKEN.

- Write the verbs again in the other textbox and consider the questions underneath.

What do the results tell you?

Would the results in the spoken register be different, if you were using an American corpus instead of the BNC?

Option 2. To understand how the two options differ from one another, let's try the second option that was presented in the tip box above. Here are the instructions:

- Use the same search string as previously

- Set Register 1 to ACADEMIC.

- Set Register 2 to SPOKEN.

- Click Search.

Good to know.

This search takes the academic register as a norm and compares the occurrence of the language items in the spoken register to their frequency in the academic register. The results are displayed in the form of a list, starting from the item that is the most common in the academic register as compared to its use in the spoken register.

Examine the search results closely. The columns Tokens in register 1 and Tokens in register 2 tell you the number of occurences of each search word in the corresponding registers. The figures in the Per million in register 1 and Per million in register 2 columns are mutually comparable, as they are independent of the size of the register. However, the most important of the columns is the one on the extreme right, titled Reg1-2 ratio. This tells you, how many times more often each word in the search string can be found in the academic register than in the spoken register. If you compare the order of the listed items to that yielded with Option 1 above, you'll notice the difference.

With POS-tags, this search option works well for contrastiong a register to an other, and examining the traits that characterise that particular register. However, understanding the search results and knowing that the listed search results are not a list of the most common words in the register is essential for being able to benefit from this search option.

We congratulate you for having completed the VIEW section of the Corpus Library. Navigate to the next section, Let's talk MICASE.

|